Death in the Desert

DEATH IN THE DESERT

My astrological sign is Aquarius, which might explain my absolute fascination with boats and boat designs since I was old enough to walk. I used to make boat hulls from cantaloupe rinds and float them down the gutter before I was in kindergarten. From the beginning, I loved the design and shape of surfboards, which caused me at 14 years old to buy a 12’ tandem board just because I thought it would be fun to take friends surfing on it.

In the early 1970’s, at the glass shop where the first Infinity boards were glassed, Geoff Prindle, the laminator, began shaping the hulls for a catamaran that he wanted to start building. Geoff had recently won the Hobie Cat 14’ national championships and was an accomplished surfboard shaper as well. As I watched the shape of the hulls emerge, I was captivated by the truly brilliant design that Geoff was incorporating. Unlike other catamarans, these hulls had a foil profile similar to an airplane wing, designed to help a catamaran “climb” up wind and release the water flow with minimal drag. I put my money down and bought Prindle Catamaran #1, nearly 3 years before production models came off the assembly line. I was the test pilot and busted a few hulls and rudders until they learned where to put additional braces for strength. Later, in 1973 when the catamaran sales became strong, Geoff and Sterling, his partner, needed to expand into a bigger building, so I bought the surfboard glass shop from them and turned it into a 100% Infinity factory. I sold the factory in 1980. It is now called Ocean Works and they still glass most of our surfboards.

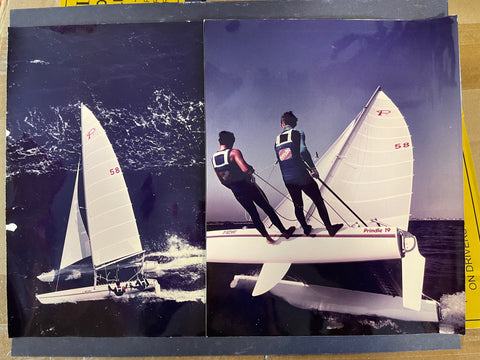

Very soon after a few of the new catamarans were sold, the Prindle factory, named Surfglass, organized and sponsored a racing fleet. It was perfect for Barrie and I because as we were learning the complicated yacht racing rules and racing techniques, the “fleet” of competitive Prindle racers grew and matured with us. Within our fifteen years of competition, some of the very best catamaran racers in the world participated in Prindle class racing. We won several Calif. State Championships on the Prindle 16 and I won a few more championships with heavier male crews on the Prindle 18 and 19 models.

Me and my crew Mino racing the Prindle 19 in the 1980’s.

One of the first races was held in 1975 at Lake Havasu on the Colorado River. My parents, Jerry and Carole plus my sister, Lisa and her boyfriend Drew Parks came along to enjoy a weekend at the lake while we raced. We got a campsite at lake side on an island accessible by the London Bridge, yes, they actually bought the London Bridge, numbered every stone, shipped it to Lake Havasu and reassembled it right there. The most fun race was around the island where you cross the finish line by passing under the London Bridge.

I forget how we did in the races that weekend, but I will never forget what happened when the racing was over. All of the other racers packed up and headed home in the Sunday night “Vegas” traffic, but we decided to stay the night and drive home on Monday. That evening, shortly after dark, a massive storm blew down from Canada. When I turned on the car radio, the local radio station announced that a powerful desert windstorm was brewing and consistent 75 mph winds were expected. All high-profile trucks, motor homes and trailers were advised to get off the freeway. Our vans were parked parallel to the beach and were shaking so violently on the bluff that we re-parked them pointed directly into the wind. I went down to the beach in the dark and lowered the sail on the catamaran just to be safe. It was impossible to sleep that night, the van felt like a bunch of angry Viet Nam war protesters were shaking it and raising hell outside.

The next morning, I got up to see the lake transformed into a nasty frothing torrent of spray and white caps. The churning water sucked the mud up off the bottom for the first three hundred yards offshore where the water was shallower. Further out, in the deep blue water, the lake was alive with whitecaps whipped into 75 mph eye blistering spray. Starting at the brown water line, the waves peeked up to 4 foot brown spitting breakers. My tandem surfboard was lying on the beach where the family had left it. I decided to paddle the tandem out and become the first person ever to surf lake Havasu.

It was interesting, I could paddle all the way out to the deep water drop off, turn around and catch a big “brown cap” all the way back to the beach. With a 75-mph tail wind, the ride was pretty fast, but the spray and chop was so miserable to paddle in, I decided that it was time to try the catamaran. I went up and recruited Drew as crew because he was a big heavy guy who could help me control the boat in the powerful wind. We rigged the Prindle without the front Jib sail and reefed the main sail down by one third. By catamaran standards, the sail area was tiny.

By this time in my life, I had surfed all over the North shore of Hawaii in some pretty big surf and of course, no surfer would dream of wearing a life jacket. I considered catamaran sailing pretty tame compared to big wave surfing. Drew was a tough x-Army soldier, just returned from Vietnam, so I didn’t even think about a life jacket for him either. We launched the cat into the fiercest wind I had ever encountered. As I sheeted in, the boat was jerked up onto one hull and flung about like a toy. I was thinking to myself: Wow, this is nuts, but since we’ve gone to this much trouble; we’ll just have a wild run across the lake and back once, declare victory, go in have a beer and forget it.

Our combined weight was 380 lb. But even with both of us out on the double trapeze wires, the cat was violently flung high up onto one hull. The screeching wind was so loud; we couldn’t hear each other yelling. Since we were sailing into the wind, much of the power of the wind was deflected off the sail. I still hadn’t really squared up against the wind in a reach or down wind run. When I got further out into the lake, I realized the whole idea was stupid. The boat was nearly uncontrollable. I decided to tack around and head back. I found that it was impossible to turn directly through the eye of the wind, so I was forced to do a down wind jibe turn. In high wind, this is a very violent maneuver on a catamaran sometimes resulting in busting up some of the parts in the rear crossbar assembly. As we jibed around, the boom swung through the eye of the wind, slammed across the rear crossbar and flipped the catamaran over like a toy boat. The wind hit the top hull and the trampoline which quickly turned the whole thing “turtle” (upside down) with the mast facing the bottom of the lake.

I don’t have a picture from that day, but here is one of a cat “pitchpoling” on a much calmer day:

From my experience in high wind sailing, I knew that there is a tremendous surface current moving down wind while several feet under water, there is no current. This means that as the hulls on the surface are driven down wind by the current, the mast and sail underwater are acting like a lever lifting the windward hull out of the water. In fact, you have to act fast to maneuver yourself underwater to the leeward down wind hull so you can hang on, as the boat will flip itself, back up-right. (As the boat becomes up-right, the leeward hull becomes the windward hull). You have got to get your body weight up onto the boat as it rights itself, or it will immediately flip over again in an endless series of out of control capsizes.

I was yelling to Drew, who was now only two feet from me to dive under the hull and swim for the other hull. He could barely hear me above the howling wind and didn’t understand what I was talking about anyway. I had only seconds to pull this off, so I dove for the “lee” (downwind) hull without him. Immediately the boat flipped back upright and with out hesitation careened up onto one hull and began to flip over again. My body weight was not enough to hold the boat down, so I dove for the tiller and turned the boat into the wind. This prevented another flip over and put the boat into kind of an “out-of-gear” stall.

Drew was swimming about 6 ft. from the side of the cat. He seemed to be stunned that the boat miraculously flipped itself upright from the “turtle” position. I yelled to him: get over here quick. All he had to do was put his head down and swim about 6 hard crawl strokes to get to the boat, but he just wouldn’t do it. He just kept dog paddling. The boat was being pushed by the wind sideways faster than he could dog paddle. Then I realized that Drew wasn’t much of a swimmer, he was slowly getting further and further away. There was terror in his eyes, and he started to panic and he began yelling:” help, help”. I knew that with out his weight on the boat there was no way that I could tack or jibe that boat around to sail back up wind to him. I’m now 20 yards away from him, his head was barely above water as the giant whitecaps washed over him and he was screaming: help, I’m drowning!!! I’m drowning!!!

I scanned my position on the lake; we were about 150 yards outside the muddy water line and 200 yards south of our camp on the beach. I knew that I only had a few minutes before Drew would drown and the only way I could get back to him was on my tandem surfboard, lying on the beach. I pulled on the tiller, pointed the cat for the beach and sheeted in. The boat took off like it was rocket powered. I knew Drew would think that I abandoned him, but it was his only hope. My parents, Lisa and Barrie witnessed the wild ride and crash; they could see that only one person was on the cat. They felt helpless. I hit the shore hard and the boat skidded about 10 feet up the beach. I ran for the tandem board and started sprint paddling as hard as I could back out into the lake.

I had this horrible sick feeling of impending disaster. I have never paddled so hard in my life, but the spray, wind and white caps made the pace seem maddeningly slow. I was thinking of his death, my sister, his parents, I was desperate. I just kept the nose of the board pounding into the waves. I felt an intense lock-up forming in my back (like a cramp in your calf), so I switched from knee paddling to prone paddling. I was heading back south and towards the edge of the muddy water. When I reached the dark water line, I stopped, sat up on the board, looked at the beach to get my position and headed further south. The water surface was wild, everything was moving, and spray filled the air.

Off in the distance about 50 yards, I caught a glimpse of Drew. He had no idea I was there. He was just inside the muddy water line where the waves were even bigger, looking shoreward and waving one arm. I screamed his name and paddled towards him, but he just disappeared under the spray and muddy waves. It was imposable to tell how far I had gone since I saw him, but when I got to where I thought he was, I could see only waves, brown spray, and muddy water. I sat up on the board and scanned in all directions, but he had gone under for the last time. It was unbelievable, I had gotten so close, but for the first time in my life I had seen someone die. The feeling inside my head was absolute failure and devastation. I was sobbing like a baby with the spray and waves washing away the tears, his life was over!

About 12” under water, my foot brushed against something fuzzy. It felt like a dead bird or rag. I looked down and barely glimpsed something in the brown water. I reached down into the water and grabbed a fist full of Drew’s long blond hair. Miraculously, I had stopped precisely in the exact spot. I pulled him up onto the board; he was unconscious and lifeless. Since he was lying across the deck of the board on his stomach, it seemed natural to push on his back to squish the water out of his lungs. Every time I did this, water gushed out. I learned later that pressing on his back might also have restarted his heart if it had stopped beating. After a couple of minutes, he became conscious, and he started coughing and vomiting. He was so weak that he couldn’t even hold onto the board. Not a word was spoken as I paddled us down wind back to the beach.

The family helped him to a beach chair. He looked horrible. He just kept saying: I died; I died. Later, when I asked him about it, he said that mentally he had given up. He had just relaxed and drifted off into kind of a dream of drowning, but it felt like it wasn’t really him drowning, just his body. His mind had departed his body and was watching the scene from a distance.

EPILOGUE:

Drew and My sister eventually split up and married other people, but he and I have remained friends. He often drives his hot rod cars to the Infinity shop and has several Infinity surfboards.

After reviewing this day over and over again in my mind, I realized several months later what I could have done when Drew first became separated from the boat. I should have turned the cat across the wind and just let it flip over again. I could have sat on the bottom of the up-wind hull and probably held the boat in the inverted position. The mast and sail would have acted like a sea anchor and since Drew was up wind from me, he would have just been blown back to the boat. At that time, I could have taken the time to explain to him the righting procedure. It’s a shame how you just can’t think of all the options when the pressure is on for an instant decision.

Old movie from that day:

I wrote this story in 1995, now in 2025 I found this old 8 mm movie from that day. It is only 2 minutes long and very poor quality, but it does show the fierce condions on the lake. Near the end you can see the catamaran upside down in the waves and then see the wind flip it back upright. then it shows me waving my arms for help as i sailed back to the beach. My father then stopped filming as he saw this emergency in progress. You can watch the video in the story below. - Steve